World’s second biggest rainforest will soon reopen to large-scale logging

The lifting of the 20-year logging moratorium in part of the Congo is fueling disputes over how the forest can be kept intact.

The Democratic Republic of the Congo is finalizing an ambitious—and risky—new plan for the future management of its rainforest, which, as the second largest on Earth after the Amazon, plays a key role in storing Earth’s carbon.

Among other measures, the new strategy will lift the long-standing moratorium on new industrial logging permits, Environment and Vice Prime Minister Eve Bazaiba tells National Geographic in an exclusive interview.

The shift comes just weeks before the November UN Climate Change Conference (COP26) in Glasgow, Scotland, where the DRC is hoping to find substantial funding for its plans. The government is seeking $1 billion for forest protections from the Central African Forest Initiative (CAFI), a coalition of donors including Norway, France, Germany, and the United Kingdom.

The move to allow industrial logging is part of a wider program to manage the forest, says Bazaiba. She emphasizes that the moratorium was a temporary measure put in place nearly 20 years ago and cannot remain indefinitely, adding that she does not anticipate approving new logging projects for the time-being, even after the moratorium is lifted.

The plan, which Bazaiba says will become law ahead of COP26, is bringing to the surface deeply entrenched disagreements over issues relating to sovereignty, development, and the safeguarding of the rainforest, the largest in Africa.

“When I speak of removing the ban, people say, ‘It’s over, Congo will award concessions to whoever.’ It’s not true,” Bazaiba says. The minister insists that the moratorium is being replaced with stronger, permanent measures for the protection and sustainable management of the forest, including the expansion of protected areas.

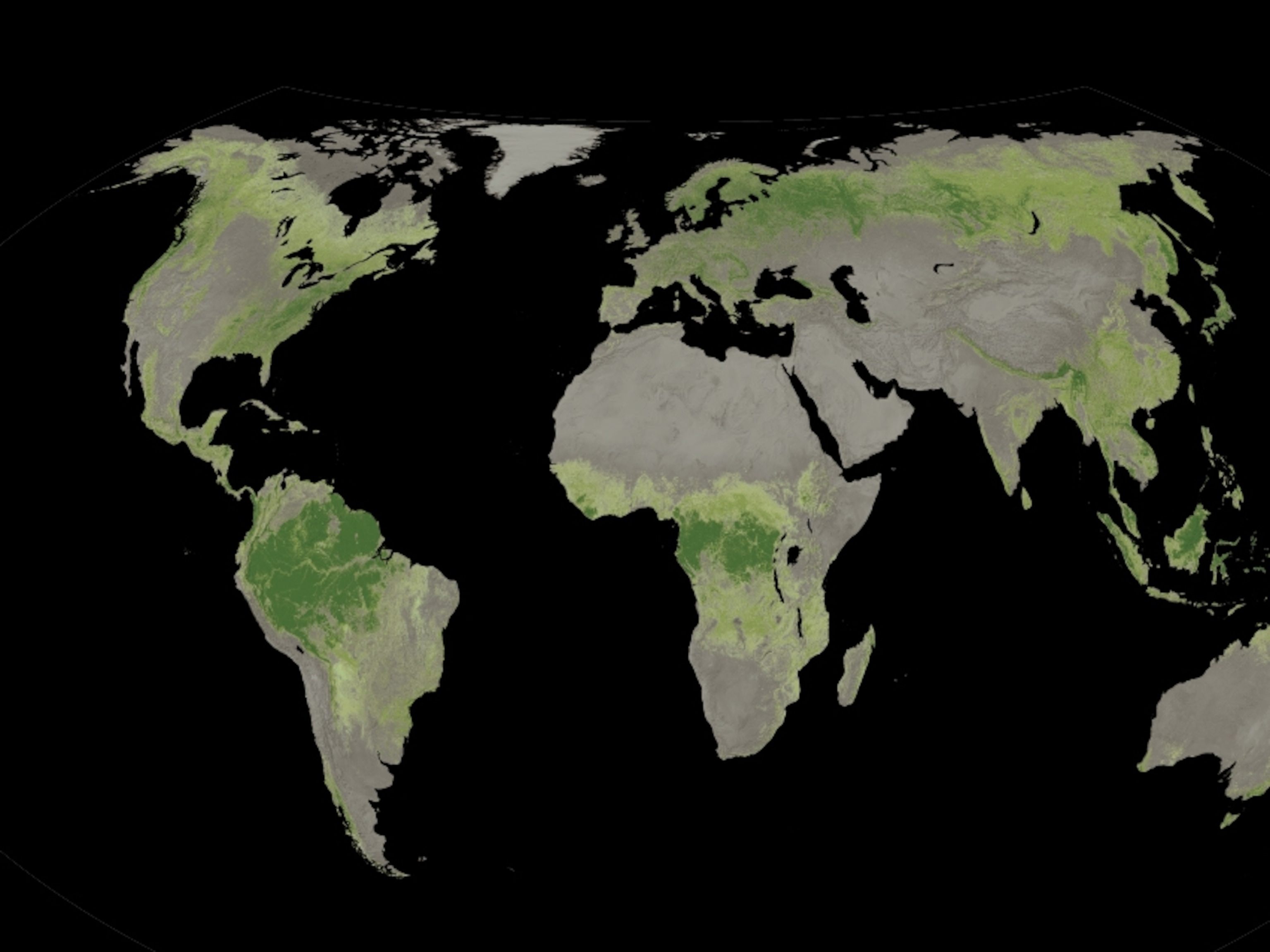

The lush rainforest that covers roughly 60 percent of the DRC makes up two-thirds of the Congo Basin. The rainforest plays a central role in the planet’s ecological balance by carrying moisture across the African continent, and it absorbs more carbon than it emits. According to a recent study, trees in the Congo Basin store a third more carbon over the same area of land compared to the Amazon.

Criticisms arise

The outline of the new plan, approved in July, has had a generally positive reception from environmental defenders and experts, since it includes the introduction of a carbon tax and the streamlining of information sharing between agencies. Some aspects also have been met with strong criticism.

Laurence Duprat, senior campaign advisor at environmental nonprofit Global Witness, feels the DRC should not allow logging until it has a land-use plan that is enforceable. Opening the forest to industrial loggers before then “would be a disaster for the rainforest and its inhabitants,” she says.

The logging moratorium was established in 2002 to protect the forest following decades of dictatorship and war. Lifting it will allow the government to award new contracts to industrial logging companies and could potentially open up as much as 70 million hectares of virgin forest—well more than half the primary forest in the DRC—to logging, according to Greenpeace, Global Witness, and a consortium of international NGOs who oppose the move.

Not everyone agrees that the moratorium has helped stave off deforestation. Between 2001 and 2020, DRC lost some 15.9 million hectares of tree cover, or 8 percent, according to Global Forest Watch.

“Some of us think focusing on maintaining the moratorium has distracted from more pressing issues, and a realistic view of what sustainably managing the forest means,” says Essylot Chishenya, the director of Observatoire de la Gouvernance Forestière, a Congolese environmental NGO dedicated to the independent monitoring of the rainforest.

“For example, there is a local demand for wood that needs to be met. It’s not just about foreign companies. Without new concessions, people are chopping down the forest illegally, without any adequate methods, plans, or checks and balances.”

Preventing a forest ‘sell-off’

The Democratic Republic of the Congo, the second largest country in Africa, struggles with a lack of infrastructure, a primarily informal economy, and weak institutions due to a history marked by colonization, dictatorship, and years of conflicts. It is estimated that less than a quarter of the DRC’s population has access to electricity. Urban demand for charcoal—the only cheap and accessible source of energy—has been fueling deforestation, as has burning forest for agriculture as population growth surges, as well as demand for lumber for construction.

From 2015 to 2019 the rate of tree felling doubled. At the current rate of loss, 30 percent of the rainforest will have disappeared by 2030 and all primary forests could be razed by 2100, according to Global Forest Watch.

The challenge facing the government to safeguard the rainforest is daunting, and authorities lack the resources to monitor what really happens on the ground. Controllers constitute a small, poorly paid workforce with few means of transportation.

“Today, the [small-scale] logging sector is much larger than the industrial sector. Large-scale [projects] are well-known and easier to monitor, and also bring in revenues for the government through taxes. So it’s easy to understand the logic for the minister,” says Chishenya.

Over the years, the moratorium has been repeatedly violated by government officials awarding more permits granting logging than rules allowed, or turning a blind eye to land grabs by powerful army officers, politicians, and businessmen.

Legal action initiated by NGOs against former environment minister Claude Nyamugabo for allegedly illegally granting logging permits for two million hectares to Chinese companies in 2018 is pending before the Council of State (Conseil d’État). An appeal has been lodged against permits awarded to Belgium-controlled TradeLink, a moved joined by the governor of the Tshuapa province, Pancrace Boongo Nkoy.

Bazaiba, who replaced Nyamugabo in April, tells National Geographic that she is reviewing the contracts and considering cancelling them. “It is practically a sell-off of our forests,” she says. “There are places where we are going to terminate the contracts and conserve the forests instead. We would gain more from having carbon credits certified in these forests than leaving them to people who exploit them without respecting our standards.”

This statement comes as Congolese President Félix Tshisekedi’s government has started cracking down on foreigners taking advantage of its lack of on-the-ground law enforcement. In the South Kivu province, local authorities put a stop to illegal gold mining by Chinese individuals in August, leading to a rare public apology by senior officials in China, with whom the DRC is currently renegotiating large-scale mining contracts.

Calls for a solid forest plan

At President Joe Biden’s Leaders Summit on Climate in March, Tshisekedi pledged to stop deforestation and restore the forest cover to 63.5 percent—up from 55.5 percent in 2020, according to World Bank data. Not everyone is convinced this will happen.

“The government keeps saying that the DRC will go to the COP26 as a ‘solution country’ to climate change, since the Congo stores so much carbon. Lifting the moratorium on new logging concessions is a direct contradiction of their stated intentions,” says Irène Wabiwa Betoko, head of the Greenpeace Africa campaign for the Congo Basin forest.

The recent discovery of the largest area of tropical peatlands in the world—which straddle the DRC and its neighbor, the Republic of the Congo—has highlighted what’s at stake. Scientists have estimated that the deposit contains 33 billion U.S. tons of carbon, as much as all the trees in the Congo rainforest—which is 13 times larger. The peatlands could be destroyed if their fragile ecological balance is destabilized, scientists say.

Congolese forest experts warn that without a detailed cross-sector plan and clear mapping of the forest’s use, Bazaiba’s ambitions could be at odds with her colleagues in the government.

“It’s not just logging; it’s mining, it’s agriculture, it’s community forestry,” says Joseph Bobia, national coordinator of Réseau Ressources Naturelles, a platform of 256 environmental nonprofit organizations in the DRC. “One of the conditions to lift the moratorium, the only one that has still not been fulfilled, is a cross-sector land use plan.”

Bobia cautions that “if there isn’t a clear understanding of how much of the forest can be logged, how much can be cleared for mining, it will be a free-for-all, maybe not with this minister, but perhaps with the next one.”

The National Geographic Society, committed to illuminating and protecting the wonder of our world, funds Gouby and Sobecki’s work on the vital role the Congo Basin plays in the ecological balance of our planet. Learn more about the Society’s support of Explorers.

Related Topics

You May Also Like

Go Further

Animals

- Soy, skim … spider. Are any of these technically milk?Soy, skim … spider. Are any of these technically milk?

- This pristine piece of the Amazon shows nature’s resilienceThis pristine piece of the Amazon shows nature’s resilience

- Octopuses have a lot of secrets. Can you guess 8 of them?

- Animals

- Feature

Octopuses have a lot of secrets. Can you guess 8 of them?

Environment

- This pristine piece of the Amazon shows nature’s resilienceThis pristine piece of the Amazon shows nature’s resilience

- Listen to 30 years of climate change transformed into haunting musicListen to 30 years of climate change transformed into haunting music

- This ancient society tried to stop El Niño—with child sacrificeThis ancient society tried to stop El Niño—with child sacrifice

- U.S. plans to clean its drinking water. What does that mean?U.S. plans to clean its drinking water. What does that mean?

History & Culture

- Gambling is everywhere now. When is that a problem?Gambling is everywhere now. When is that a problem?

- Beauty is pain—at least it was in 17th-century SpainBeauty is pain—at least it was in 17th-century Spain

- The real spies who inspired ‘The Ministry of Ungentlemanly Warfare’The real spies who inspired ‘The Ministry of Ungentlemanly Warfare’

- Heard of Zoroastrianism? The religion still has fervent followersHeard of Zoroastrianism? The religion still has fervent followers

- Strange clues in a Maya temple reveal a fiery political dramaStrange clues in a Maya temple reveal a fiery political drama

Science

- NASA has a plan to clean up space junk—but is going green enough?NASA has a plan to clean up space junk—but is going green enough?

- Soy, skim … spider. Are any of these technically milk?Soy, skim … spider. Are any of these technically milk?

- Can aspirin help protect against colorectal cancers?Can aspirin help protect against colorectal cancers?

- The unexpected health benefits of Ozempic and MounjaroThe unexpected health benefits of Ozempic and Mounjaro

- Do you have an inner monologue? Here’s what it reveals about you.Do you have an inner monologue? Here’s what it reveals about you.

Travel

- Follow in the footsteps of Robin Hood in Sherwood ForestFollow in the footsteps of Robin Hood in Sherwood Forest

- This chef is taking Indian cuisine in a bold new directionThis chef is taking Indian cuisine in a bold new direction

- On the path of Latin America's greatest wildlife migrationOn the path of Latin America's greatest wildlife migration

- Everything you need to know about Everglades National ParkEverything you need to know about Everglades National Park