Fires continue to rage at high levels through the Amazon in Brazil for the second consecutive year, raising concerns among scientists that the rainforest’s destruction could eventually reach a point of no return.

Since Brazilian President Jair Bolsonaro took office, governmental measures to curb illegal fires have shown little impact, as flames and deforestation erase vast swathes of the world’s biggest rainforest.

Most fires in the Amazon are set by land-grabbers and wildcat ranchers, seeking to transform parts of the rainforest into their own lucrative agricultural enterprises. And this August was a particularly bad time for such fires: Preliminary data collected by the National Spatial Research Institute (INPE) show 29,307 fires in the Brazilian Amazon last month.

However, due to a technical issue with the NASA satellite tracking fires, experts say that figure could be even higher. The final tally of fires recorded in August is expected to rise 2% above the August 2019 total, says Albert Setzer, INPE’s senior scientist – which would make this August the worst in 10 years.

The more fires there are, the faster the rainforest is transformed into grasslands for illicit cattle and soy-growing operations. According to research from NGO MapBiomas, which tracks land use in Brazil, 95% of the deforested area in Brazil in 2019 wasn’t authorized. “Most of (the fires) are illegal,” said Tasso Azevedo, a former head of Brazil’s forest service and coordinator of MapBiomas.

Deforestation in the Brazilian Amazon biome reached 1,830 square miles, an area bigger than Rhode Island state, in the period from January to July 2020,. August figures for deforestation are yet to be released.

A tipping point?

As the trend goes on, the Amazon is speeding toward a tipping point, when large areas of the rainforest will no longer be able to produce enough rain to sustain itself, according to Carlos Nobre, one of Brazil’s leading climate scientists and researcher at the University of Sao Paulo.

Once that happens, the rainforest will begin to die, eventually turning into savannah, said Nobre.

The Amazon serves as an “air conditioner” for the planet, scientists say, influencing global temperature and rainfall patterns. And a healthy Amazon also absorbs carbon dioxide, while fires do the opposite, releasing massive quantities of heat-trapping carbon dioxide into the atmosphere.

The Brazilian Amazon’s deforestation has accelerated since Bolsonaro took office in 2019, and environmentalists accuse the president of encouraging development on protected lands.

Pressure from international investors and companies this summer pushed the Brazilian President to issue a 120-day moratorium on July 15, banning fires in the Amazon and in the Pantanal, which is the world´s largest wetland area.

However, INPE´s data appears to show that the ban was utterly ignored. From July 15 to the end of August, the fires in Amazon remained at the same level (around 35,000) and almost quadrupled (from 2035 to 7320 fires) in the Pantanal, compared to the same period in 2019.

Brazil also launched Operation Green Brazil 2 in May, which mobilized the Armed Forces to fight deforestation and fires in the Amazon together with the federal environmental agencies and local police forces.

But they too failed to halt the Amazon’s destruction, acknowledged Vice-President Hamilton Mourão, who led the operation. “We are late in the fight against deforestation,” Mourão said in a Sept. 4 press conference, asking for more time to show results.

The last frontier: Amazonas

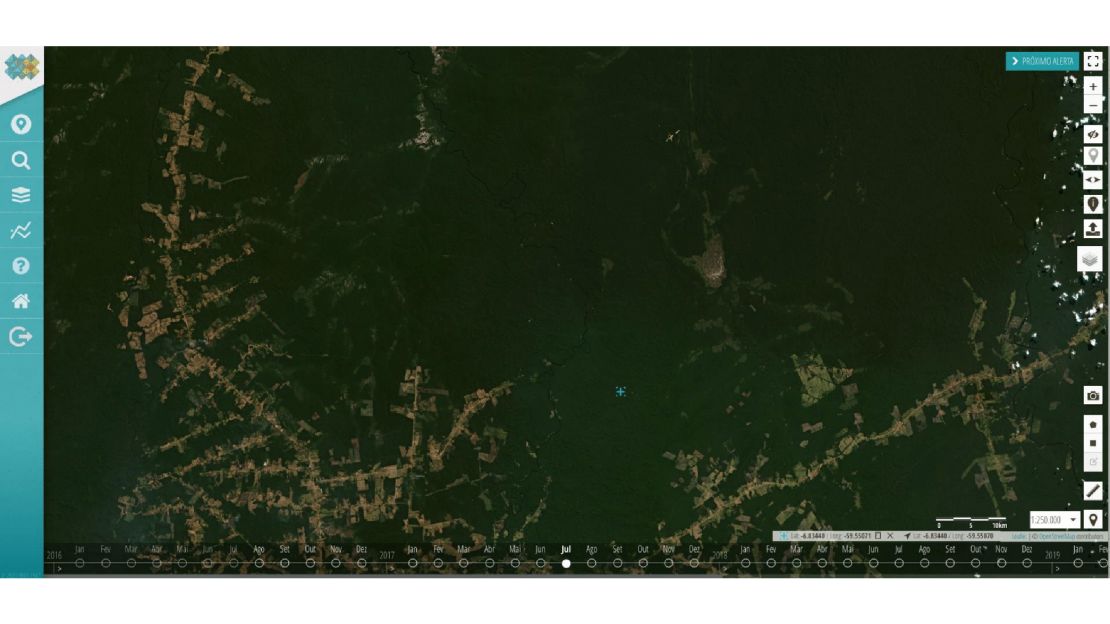

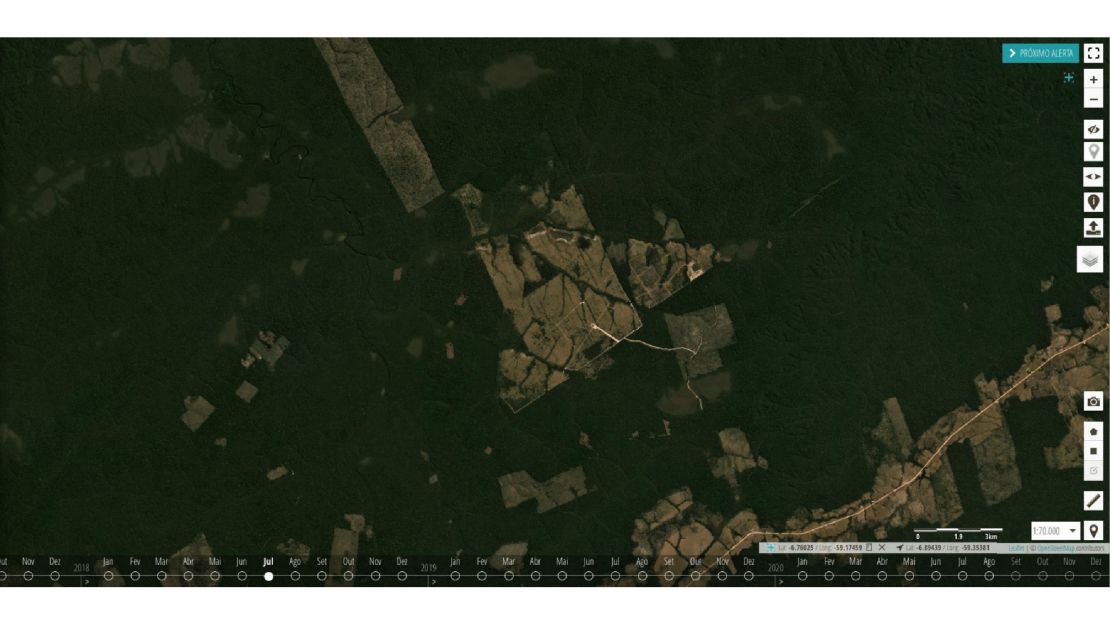

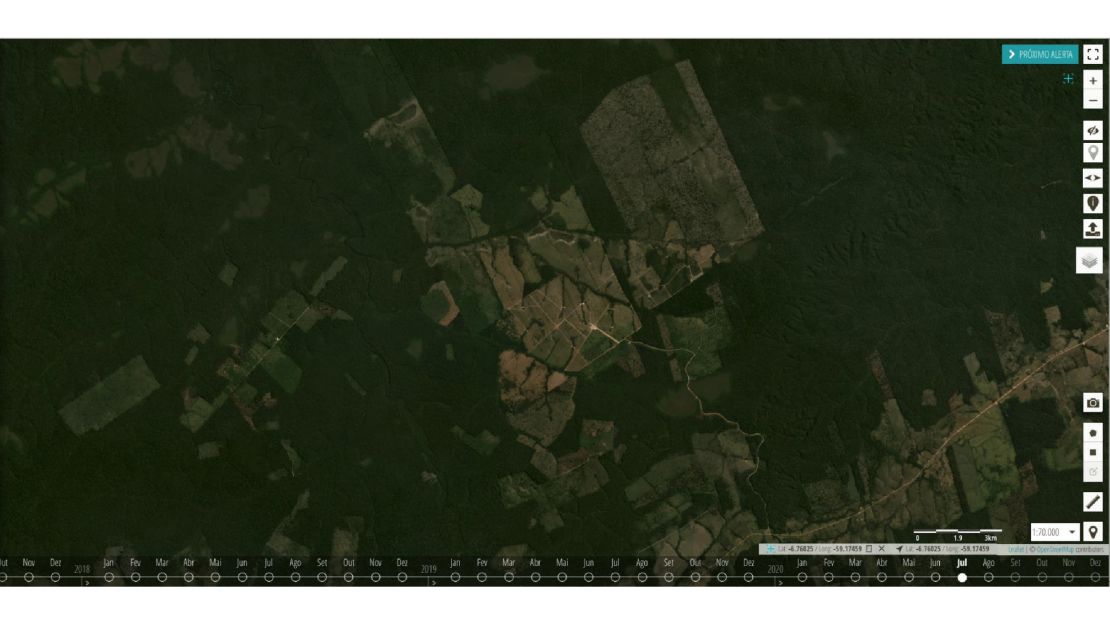

The Brazilian state of Amazonas is one of the last frontiers where forests remain mostly preserved. But even there, illegal operations of loggers and ranchers are expanding.

Deforestation has grown 209% in Amazonas state since Bolsonaro took office – erasing 844 square miles of forest in less than two years.

Unregulated agricultural expansion drives local small farmers and ranchers further into the forest every year. “The lands that are closer to the main roads are more concentrated in the possession of a few big landowners, so landowners with less economic power are pushed further into the forest, whether by economic pressure, political pressure or by the use of violence,” said Rômulo Batista, senior forest campaigner of Greenpeace.

The most degraded areas border two federal highways in the south of Amazonas. In the city of Apuí, near to the junction of both roads, deforestation reached 110 square miles last year – almost twice the deforestation of 2018.

And every time the agricultural frontier is pushed inside the forest, the Amazon gets closer to its tipping point.

One symptom of the accelerating deforestation is longer dry seasons, Nobre said. This will initially be felt in Brazil and elsewhere in South America, as the Amazon generates a great part of the rains for the rest of the country, and also affects the rains in neighboring Paraguay, Uruguay, and Argentina.

And even farmers and ranchers will feel the consequences. “This ‘savannah-ization’ of the Amazon will lead to a reduction in rainfall that will affect especially the agricultural sector, which is driving deforestation further. It’s a real shot in the foot,” Batista said.

If the Amazon one day disappeared altogether, Brazil’s rainfall on average would be reduced by up to 25%, predicts one modeling exercise by researchers at Princeton University. Average temperatures would also be expected to rise 2 degrees in Brazil and 0.25 degrees worldwide.

Nobre predicts that the tipping point for when the Amazon can no longer sustain itself lies between 20% and 25% of deforestation. So far, it has lost 17% of its original area, according to INPE.

“It’s hard to say when it’s going to happen, but we are seeing that it is coming faster than we previously thought,” Nobre said.