Duong Thi Canh lives near the sea at Hai Phong village in Ky Loi commune, Ha Tinh province. Her home is about 500 meters from Vung Ang 1 coal power plant in central Vietnam.

“Since the operation of Vung Ang 1 coal power plant and Formosa, the air has not been as fresh as it was,” says Canh. The Formosa Ha Tinh Steel plant uses four coal turbines to generate its power.

In the words of Canh, in the northeast summer monsoon, the air becomes worse. She feels her breath being covered by a thin net of dust. The dust comes from different wind directions. It can come from the Formosa plant or Vung Ang 1 station. In the evening, locals see black ash flying from their chimneys.

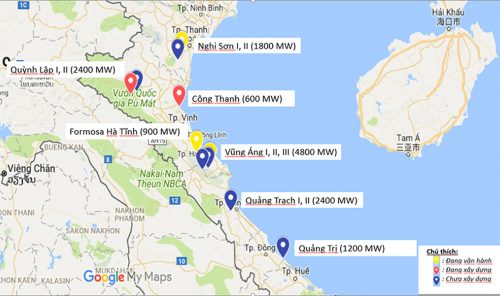

Vietnam currently has 20 coal power plants in operation, accounting for about 35% of country’s total electricity generation. According to the country’s revised Power Development Plan which looks towards 2030 — known as PDP 7 revised — Vietnam plans to have 66 coal power stations, accounting for 53.2% of the total electricity generation.

Like other families in Hai Phong village living close to coal power plants, Canh has been worried about cancer. She hasn’t cooked food with rain water from her roof. She has also not used her well water after its color changed several years ago. Her family spends about one million VND (around $43 USD) a month to buy water. Her six-year-old child often suffers from itches and a cough.

Her husband passed away 10 years ago. Canh takes care of her four kids alone. Apart from selling vegetables, chicken, and ducks, she owns a small beer shop. Being categorized as a poor household, Canh receives health insurance from the Formosa company after the disaster in April 2016, when an underground pipe near the steel mill spewed dark yellow water. Masses of dead fish washed ashore on beaches in Ha Tinh province.

From the insurance she can receive free healthcare and drugs if she is ill. “If I had a choice, I would have chosen a clean environment instead of the free healthcare,” she says.

Canh’s case is not an exception in Hai Phong village. Almost all the locals share the same wish. Chu Van Bon, a fisherman’s wife, has suffered from thyroid cancer for years. Since the air degradation, it has been more difficult for her to breathe.

Between 2018-2022 Vietnam plans to generate 34,864 megawatts (MW) from all energy resources, with coal power accounting for about 75% of the expected electricity generation. Current construction of seven coal-fired power plants will add 7,860 MW to the national plan, but another 18,000 MW is still needed.

In the Nghi Son Economic Zone there are cement factories, an oil refinery and petrochemical plants. Nghi Son 1 coal station is only 500 meters from the residential area in Hai Ha commune, Thanh Hoa province, central Vietnam. Nguyen Trong Hau, Vice Chairman of Hai Ha People’s Committee, says that the plant has “polluted the water and air. Its coal ash has affected the daily life of locals” for five years.

Le Thi Hiep, a resident, says that she has to close her doors and windows all day because of coal ash. She cannot sleep at night. It smells so bad that she has to wear a mask to sleep. She often has a sore throat and she is worried about her little kids most.

After residents complained about the air pollution, the local authorities did their own investigation and found that “pollution indexes are allowed.” Therefore, locals continue to suffer from the air pollution. Hau added that leaders of Nghi Son coal station had promised to equip a system of moisturizers for filtering polluted air, and to hang a flag for identifying wind directions and then rescheduling the plant operation. Until now, the air has never been clean.

INCREASED ILLNESS

Several healthcare centers in the surrounding areas of the coal stations say that there has been an increase in heart disease, stroke, lung disease, skin problems and cancers.

In Ky Loi commune, records from 2017 and 2018 documented 116 cases of heart disease and stroke. In 2017, there were eight cases of cancer. In the first four months of 2018, there were six other cases of cancer. In 2017, from August to November, two cancer patients and12 suffering from heart disease and strokes died.

Hai Ha commune has 11,000 residents. Between 2013 and 2017, up to 45% of deaths annually were from cancer. These high rates are alarming according to Dr. Nguyen Trong An, Deputy Director of the Research and Training Center for Community Development (RTCCD). Vietnam’s cancer rate is quite high in comparison with the average rate of the world.

“Air pollution can be one of the major causes,” says Dr. An.

RESETTLEMENT AND RESISTANCE

Ky Loi commune will disappear from the administration map as its 9,900 residents will be resettled. Their land will be confiscated for planned coal stations. Chu Van Quang, Vice Chairman of Ky Loi People’s Committee, says that it is very difficult for those who are resettled to find jobs.

Following resettlement, they do not have farmland. Old people and women do not have their own livelihoods. Until now, only 100 people have been recruited by the Formosa corporation and around ten are working at the Vung Ang 1 coal power plant, accounting for less than 1% of the commune’s population. The majority of young people migrate to big cities for jobs.

Hai Ha commune will also disappear from the administration as its land will be allocated for industrial projects, including planned coal power plants. Locals agreed to vacate their rice and salt fields but their main income has depended on fishing. Following resettlement many fishermen migrated to big cities for manual work or selling lottery tickets. But some of those who resettled sold their new land and returned to Hai Ha to fish.

Nguyen Trong Hau, vice chairman of Hai Ha People’s Committee, says that over 500 households were resettled in Hai Binh commune. However, only 100 households remain there.

“My husband and I returned (to) Hai Ha. My husband still goes fishing. I sell fish because my salt farm was confiscated for coal stations. Our family members have been fisherpeople for generations,” says Ms. Tuoi.

Hai Ha’s traditional fishing port will be converted to a coal port for the Nghi Son 2 coal power plant. Fisherman Vu Van Linh said that this threatens the livelihood of locals and he protested against the plant in May 2018. Fishermen also say the new proposed fishing port is not ideal for docking ships.

Residents have organized a schedule to guard their fishing port and are often confronted by security officials. As of January 2019, the port dispute between fishermen and the local authorities has not been resolved.

Nguyen Trong Hau, Vice Chairman of Hai Ha People’s Committee, feels impotent as he acknowledged the community burdens caused by coal powered plants. “When there are more plants, the air is polluted, residents cannot adapt and then they have to leave.”

The frustration of local officials is also felt in other communes. Two coal power plants — Quynh Lap 1 and Quynh Lap 2 — are planned for Quynh Lap commune in Quynh Luu district, Nghe An province.

Mr. Le Ba Van, Chairman of Quynh Lap People’s Committee, says that land clearance for these plants missed the 2017 deadline. Due to an unclear resettlement and compensation plan, residents have not agreed to leave. Locals have organized protests to defend their rights to a suitable resettlement area, compensation, and to maintain their traditional fishery and a clean environment.

Local communities in Vinh Son village, Quang Dong commune, in Quang Binh province are currently faced with land confiscation by local authorities for two coastal coal power plants — Quang Trach 1 and 2.

HUNGER FOR ELECTRICITY

The Ministry of Trade and Industry and Vietnam Electricity (EVN) believes that coal power still plays a key role to ensure the national energy security. They say that hydropower plants are generating maximum capacity while other power resources such as gas-fired electricity are still limited. Electricity from renewable energy has not been sufficient to sustain the grid–level system. They warn of energy shortages in the next five years as the opposition against coal power at the provincial level has delayed the planned construction of new coal stations.

A December 2018 report titled “Vietnam’s Crisis of Success in Electricity”by David Dapice of Harvard University in collaboration with Vietnamese experts at the Fulbright School of Public Policy and Management says that Vietnam has used electricity too inefficiently.

According to the report, the annual growth rate of electricity demand has been 12%, faster than any other comparable Asian economy and is projected to be 8-9% annually out to 2030. Due to this inefficient energy use, Vietnam requires twice as much electricity to produce the same amount of real GDP as Thailand. It uses more electricity per unit of output than China does. Vietnam’s coal use in the last five years grew 75%, faster than any other country in the world.

SAY “NO” TO COAL POWER

Environmental risks and conflicts caused by resettlement are the root causes of why provincial authorities do not want to build coal-fired power plants. In July 2018, Vice Minister of the Ministry of Trade and Industry Hoang Quoc Vuong told General Secretary Nguyen Phu Trong during a meeting: “It is very difficult to identify locations for coal stations because almost (all) provinces say ‘no’ to coal power plants.”

The Formosa coal station projects are expected to be completed in 2025. Along with the four other plants in the area — Vung Ang 1, Vung Ang 2, Vung Ang 3 and Vung Ang 4 — the Ha Tinh Department of Environmental Protection says that industrial emissions will reach 7.4 million tons per year. This will comprise of 1.8 million tons per year of ash and slag waste, and 5.6 million tons per year of mud, dust, steel slag, blast furnace slag and other types of industrial waste.

Dang Ngoc Binh, Vice Director of Ha Tinh Department of Environmental Protection, is concerned about the environmental limitations. His department submitted requeststo the Ministry of Environment and Natural Resources (MONRE) asking them to research and evaluate the air and sea at Vung Ang economic zone as well as the rivers. The assessment would help provincial authorities make decisions whether or not it should attract future heavy industrial projects. Until now, there has been no response.

Nguyen Dinh Loc, Vice Director of Ha Tinh Department of Trade and Industry, says that a master plan of the province toward 2050 has been discussed with a focus to develop tourism services and supporting industries, taking advantage of its long coastal zones and historical relics.

“We proposed the Ministry of Trade and Industry to consider the development trend of renewable energy instead of coal power,” says Loc.

Dapice says renewable energy comes at a high price tag in Vietnam, making costs of solar and wind electricity at least double. “First, land has been allocated or licensed by provinces to too many without the track record or finances to develop it. Second, there are high feed-in tariffs and limited grid capacity.”

Domestic gas production is taxed heavily even though it is a cleaner fuel, while imported coal is hardly taxed at all. Dapice says that “the only way for renewable energy to play as large a role as in other countries is by lowering its costs and improving the grid… so that solar and wind electricity can profitably be sold for less than coal.”

“Working on ways to integrate renewable energy with existing sources, and supplementing storage with batteries, would help Vietnam reach higher economic levels of renewable energy,” Dapice says.

“In comparison with coal power, gas and renewable energy take less time and capacity can be tailored to demand,” explains Dapice. “It takes 3-5 years to complete a coal plant, they are a 30 to 40 year investment, and it is hard to stop construction once started.”

COAL STATION CONSTRUCTION CONTINUES

Nghe An province has two coal stations planned — Quynh Lap 1 and Quynh Lap 2. Nguyen Huy Cuong, Vice Director of Nghe An Department of Trade and Industry, is worried about a shortage of domestic coal and having to depend on imported coal.

Cuong says local representatives often proposed stopping coal power in the meetings with voters. The potential to develop renewable energy, such as solar power, in Nghe An is very high, especially for summers. Yet the decision comes from the central level government.

Nguyen Thi Minh Hue, Vice Director of Thanh Hoa Department of Environmental Protection, recommends the government should avoid building coal stations in historical residential areas. This can help to avoid conflicts regarding livelihoods, social security, historical and cultural values, and environmental pollution.

Although Vietnam has increased policies focusing on environmental protection, there is still a gap between policies and their practices. To narrow this gap, experts say that it should both improve policies of environmental protection and promote information transparency and ensure community-based control.

Nguy Thi Khanh, Director of Green Innovation and Development Centre (GreenID), an NGO promoting sustainable development and renewable energy sources in Vietnam, said a 2011 study showed no evidence of voices of local people in the designing of power master plans and policies by the government. She says, “Individuals and communities should be actively consulted for local development projects because they play a crucial role in the prosperity of provinces and the whole country.”

A NEW PATH FORWARD?

In January 2019, the Central Economic Commission (CEC) hosted a climate change, energy security, and sustainability workshop with local and international organizations. Experts recommended that Vietnam reduce its coal dependence and speed the development of renewable energy.

As of August 2018, the Ministry of Trade and Industry said 121 more solar power projects both at the provincial and national levels were added to the PDP 7 revised. Their expected power generation in 2020 will be 6,100 MW. For grid connected rooftop solar power projects, there are 748 projects being implemented with the total capacity of 11.55 MW.

In the current context of energy development based on the PDP 7 revised, experts recommend focusing on improving the national power security strategy.

“The PDP 7 revised is only a part of an unfinished painting. There are two other significant factors — the management of ‘demand’ or power consumption, and the organization and control of the power market. These factors are not included in the PDP 7 revised,” says Nguyen Quang Dong, Director of Institute for Policy Studies and Media Development.

AN HONEST DISCUSSION

What should provincial authorities do in order to ensure national power security and sustainability while not depending on coal power?

Dapice says that the Ministry of Industry and Trade should be put under pressure from the Central Committee and Parliament to allow more grid investment to carry renewable energy to where it is needed. Allow the integration of renewable energy with existing gas and hydro power sources through better grid management. But for the local government, just saying no to coal is about all they can do.

“I hope there is an honest discussion about these issues,” Dapice says. He cites India as an example. “Renewable electricity (unsubsidized) is now selling for 3.5 cents a kilowatt hour and causing coal investments to be cancelled is instructive.”

Reporting for this story was supported by a grant from Internews’ Earth Journalism Network and the South East Asian Press Alliance. A Vietnamese-language version (Part One and Part Two) of this story appeared in Vietnam’s Nguoi Do Thi (City Dweller).