Videos of plastic waves hitting pristine waters in Southeast Asia and the Caribbean shocked the world. Those images soon became viral, making us wonder: How did plastic end up there? How can we stop this?

Of course, plastics don’t just “end up” on developing countries’ shores. It all starts with fossil fuels being extracted and transformed into new plastic products. After their use, which often lasts for only a few minutes, they are thrown “away.”

But this plastic doesn’t just disappear. Wealthier countries have been producing and exporting millions of tons of plastic waste to developing countries for the past two decades. Top exporters include the EU-28, US, Japan, Mexico, and Canada, as well as Hong Kong (the entry point for plastics waste flows to China). Many of the receiving countries don’t have the capacity to deal with this waste in an environmentally sound manner, and the plastic ends up polluting oceans and local communities.

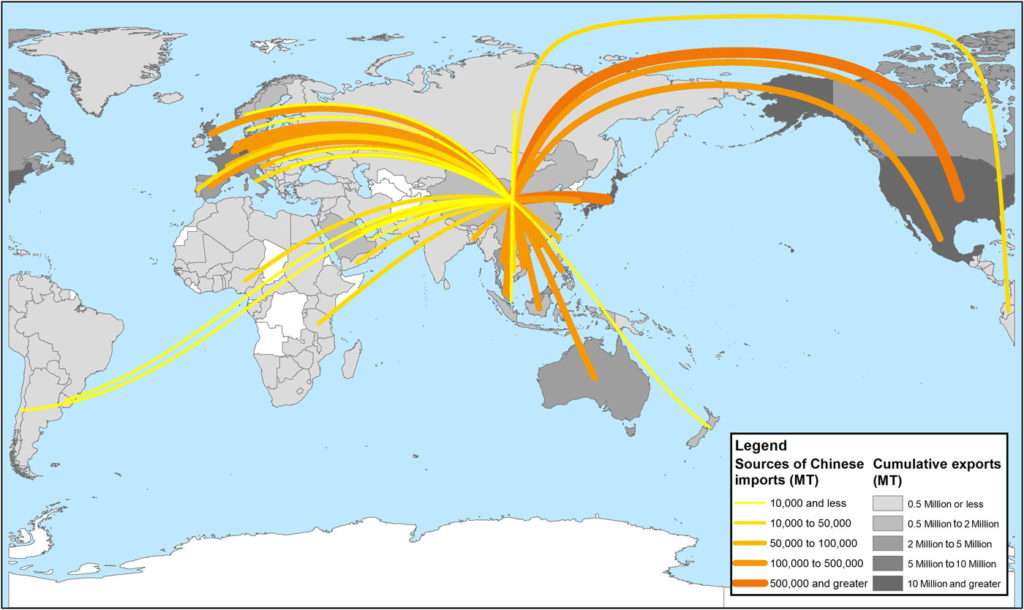

Sources of plastic waste imports into China in 2016 and cumulative plastic waste export tonnage (in million MT) in 1988–2016.

Countries with no reported exported plastic waste values are white. Cumulative exports represent by country exports of PE, PS, PVC, and other plastic [UN Comtrade data; (9–12)]. Quantities for sources of Chinese imports include PE, PS, PVC, PP, and PET (13).

What does international law say about it?

One of the international agreements most relevant to plastic waste management is the Basel Convention on the Control of Transboundary Movements of Hazardous Wastes and Their Disposal. It is an internationally binding agreement with 186 parties, meaning that almost all countries in the world have ratified the agreement, including all top plastic waste exporters except the United States. The Convention’s objective is to protect human health and the environment from hazardous waste, and it was adopted as a reaction to “toxic trade,” where industrialized countries were treating developing countries like trash bins for their unwanted — often dangerous — waste.

While the Basel Convention deals with several issues relevant to plastic waste, most plastic waste is not subject to the Convention’s provisions, unless it exhibits specific hazardous properties or is considered “household waste” under the Convention. Additionally, the Convention merely restricts the transboundary movement of the waste that is covered, but contains no provisions on indicators, timelines, or targets to reduce plastic waste.

In line with their role as a leader on the issue of marine plastic pollution, Norway has recently proposed to amend the Basel Convention to address plastic waste more effectively. The proposal will be discussed at the Convention’s Open-Ended Working Group meeting in Geneva in the first week of September. Countries will decide whether to recommend the amendment for adoption at the next Conference of the Parties of the Basel Convention in May 2019. CIEL will be at the meeting, working with partners to convince Parties to the Convention to support the Norwegian proposal.

How would the amendment work?

The proposed amendment would reclassify plastic waste under the Basel Convention. Practically, plastic waste would be moved from one Annex of the Convention to the other, by:

- Deleting ‘Solid Plastic Waste’ from Annex IX of the Convention. When waste is included in this annex, it’s considered non-hazardous unless specific conditions apply. Without the amendment, countries are free to ship plastic waste around the world as “green” waste.

- Adding a new category of plastic waste under Annex II of the Convention as a category that requires special consideration, which would oblige countries exporting plastic waste to get the prior informed consent of the receiving party. In other words, before a country would be allowed to ship plastic waste, it would have to notify prospective countries of import and transit and obtain their written consent.

The amendment would be a key tool for the countries most threatened by plastic pollution to protect their environment and population. It would give importing countries, which are often developing countries, the right to make informed decisions and the possibility to refuse polluted or mixed plastic waste that they cannot safely manage. Overall, the amendment could help reduce plastic pollution, by preventing the vast amount of plastic waste sent to countries that don’t have the capacity to manage it in an environmentally sound way.

This is of even greater importance in light of the Chinese ‘‘National Sword” policy, which bans most plastic waste imports. China was the first importer of plastic waste in the world, taking almost half of the world’s plastic waste traded globally. As a reaction to the Chinese ban, the wealthiest exporting countries have not reduced their production of plastic and plastic waste. Instead, they have redirected their huge flows to other developing countries, such as Malaysia, Vietnam, and Thailand, increasing the plastic pollution crisis. The amendment would be a strong incentive to change our “business-as-usual” approach to plastic waste, forcing wealthy countries (like the EU-28 and the US) who produce most of the world’s plastic to take better responsibility for environmentally sound disposal and stop shifting the health and environmental impacts and associated costs onto developing countries.

This change to the Convention would also greatly increase transparency, leaving a paper trail for every shipment of plastic waste and allowing for more accurate data and monitoring.

Is this all?

While the Basel Convention is considering options to further address marine plastic litter and microplastics, it’s not a magic formula. It still has a limited scope compared with the whole lifecycle of plastic and its impacts on the environment and people’s health. Waste management deals only with what happens to plastic after it’s used and discarded. But countries should be working to reduce plastic production and consumption in the first place.

Other relevant agreements exist, but there is no coordination mechanism between them. Most importantly, there is still no internationally binding agreement that addresses plastic pollution across its lifecycle, from the extraction of fossil fuels to (marine) plastic waste, and primarily aims to reduce plastic production.

More can still be done. For this reason, countries have been discussing ways to combat marine plastic litter and microplastics under the United Nations Environment Assembly (UNEA), the world’s “parliament” of the environment. Next year, they will not only have the possibility to amend the Basel Convention, but also to give the mandate to negotiate a new framework to address plastic pollution at the fourth meeting of UNEA.

If countries are serious about #BeatingPollution, they should promptly adopt the Basel Convention amendment and a new mandate to negotiate an agreement to end plastic pollution.

By Giulia Carlini, Staff Attorney

Originally posted on August 30, 2018