The European commission is planning to relicense a controversial weedkiller that the World Health Organisation believes probably causes cancer in people, despite opposition from several countries and the European parliament.

In 2015 the International Agency for Research on Cancer – WHO’s cancer agency – said that glyphosate, the active ingredient in the herbicide made by agriculture company Monsanto and used widely with GM crops around the world, was classified as probably carcinogenic to humans.

It also said there was “limited evidence” that glyphosate was carcinogenic in humans for non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma. At the time Monsanto said it could not understand the decision and that the scientific data did not support the conclusion.

The finding has triggered an EU row over the use of glyphosate, with Italy, France, Sweden and the Netherlands opposing its relicensing in March. More than 1.4 million people have signed a petition calling for the chemical to be banned.

But a leaked proposal from the European commission, seen by the Guardian, has few substantive changes from the one that was blocked last month. It would cut the authorisation period for glyphosate from 15 to 10 years, and mandate consideration of an immediate ban if a European Chemicals Agency (ECHA) study next year finds it hazardous.

The Green party called it a betrayal of the precautionary principle which obliges regulatory caution if there is scientific doubt. Bart Staes, the Green party’s environment and food safety spokesman, said: “It is scandalous that the commission is seeking to bulldoze through an EU approval for glyphosate to be used with no restrictions, despite the very serious concerns about the impact of this toxic substance on public health and the environment. Banning glyphosate would be the responsible course of action”

European agricultural industry groups said that they too were concerned that a precedent could be set by any decision to reduce the new approval period. Graeme Taylor of the European Crop Protection Agency told the Guardian: “Clearly we are disappointed that political pressure has resulted in the scientific process for substance authorisation being undermined. If the substance is considered to have met all the criteria for re-approval then it should re-approved for a period of 15 years.”

A spokesman for the Glyphosate Task Force, an industry body linked to Monsanto, said: “We would be surprised if the Commission has indeed included such terms in the draft implementing act for glyphosate. The Commission has granted 15 years in all previous cases of the renewal of active substances. We see no reason why glyphosate should be treated differently”.

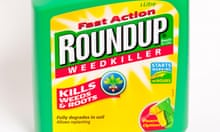

Glyphosate is an ingredient in Monsanto’s bestselling Roundup brand as well as in herbicides manufactured by Syngenta and Dow. The chemical is typically mass-sprayed on crops that have been genetically engineered for immunity, and some farmers say it has triggered an explosion of resistant weeds in the US since its introduction in 1974.

The weedkiller’s popularity ballooned 20 years ago when the US Environmental Protection Agency loosened its safety rules, allowing 50 times more residues to be sprayed on corn. Since then glyphosate’s use in the US has increased 15-fold.

WHO’s cancer arm has deemed it “probably carcinogenic to humans”, although the European Food Safety Authority disagrees. An opinion from the ECHA panel could resolve a dispute over lab methodologies and industry influence between the two scientific bodies. But the study will take 18 months and has not yet begun. An ECHA spokesman would only say that “currently, ECHA has no opinion on changing the classification of glyphosate”.

Although the commission is bound to follow ECHA’s guidance, some countries made an explicit reference to this – and a cut in the authorisation period – conditions for their support.

A diplomat from one of the dissenting states told the Guardian: “We understand from our contacts with the commission that it is willing to meet our conditions. I am not sure if those are already met in this paper but in the end, that is what we expect the commission to do.”

Last week, the European parliament voted to oppose the approval of glyphosate where alternative methods exist, and in pre-harvest agricultural use, in public parks and in playgrounds. Dozens of MEPs volunteered to give urine samples for glyphosate testing shortly before the last parliamentary vote.

Glyphosate is so widely used that it is found in British breads, German beers and in urine samples across Europe, at levels that can be five to 20 times above the safe limit for drinking water.

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion